Becoming Monsters

Guest editor Meg Jones Wall introduces The Rebis, Volume 4

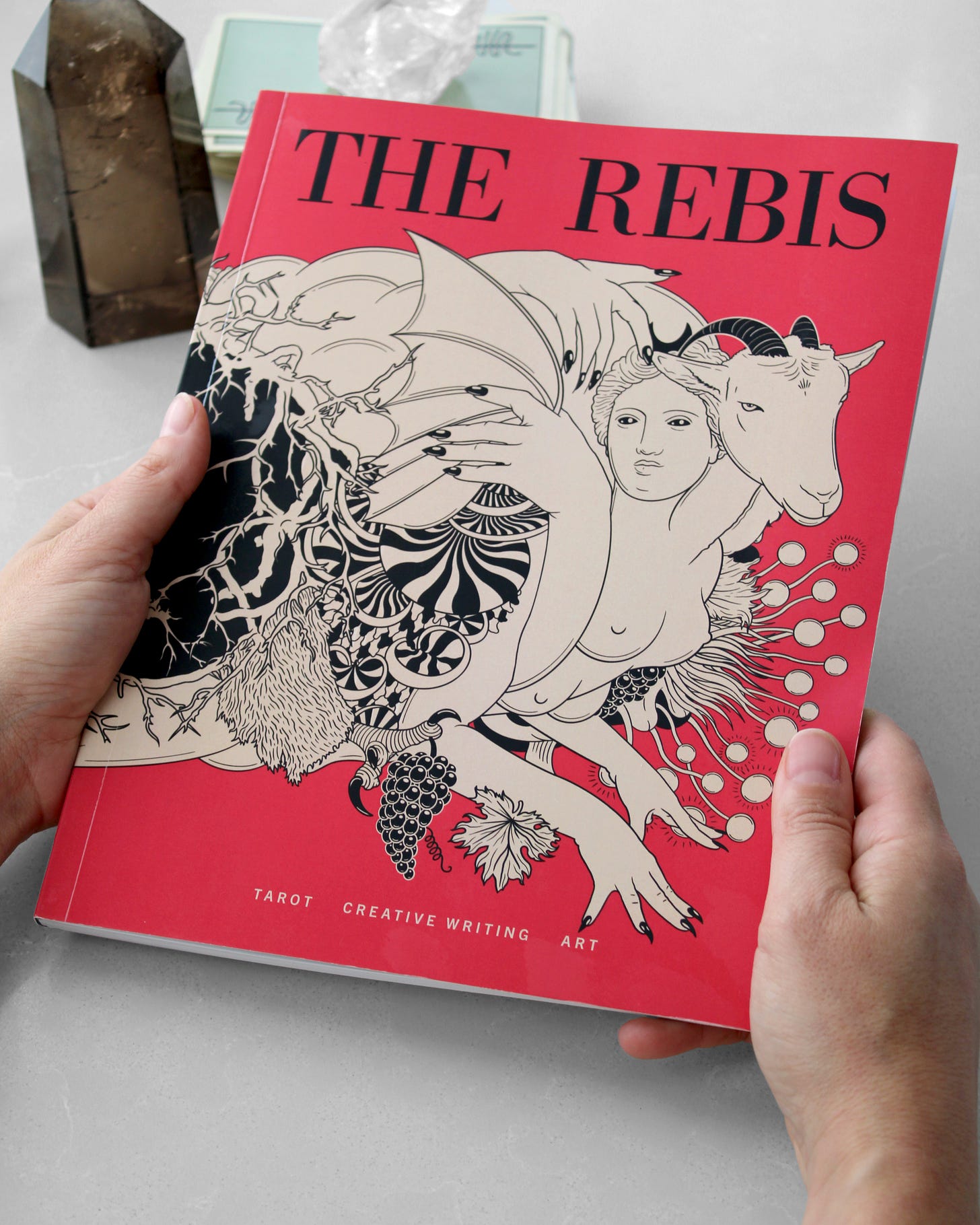

Today, we’re publishing the editor’s note from The Rebis, Volume 4: The Devil, written by our guest editor . Our new print issue features more than 38 writers and artists exploring themes of The Devil. Preorders are currently open and the publication will ship out in early October. You’ll get a beautiful full-color 8x10 book with 120 pages of personal essays, creative nonfiction, erotic fiction, poetry, interviews, and original artwork. We redistribute all profits to social justice orgs.

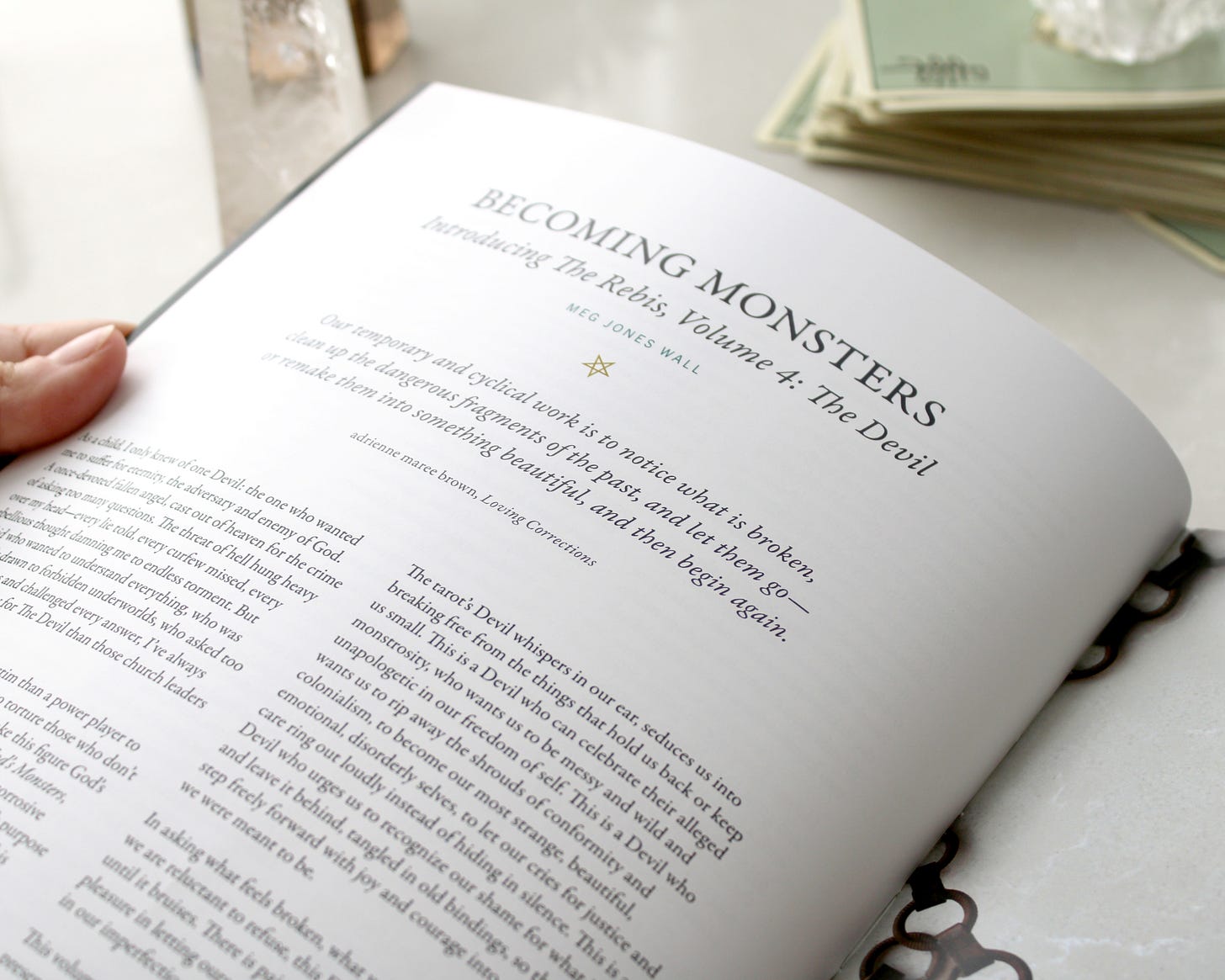

Becoming Monsters

Introducing The Rebis, Volume 4: The Devil

by

“Our temporary and cyclical work is to notice what is broken, clean up the dangerous fragments of the past, and let them go—or remake them into something beautiful, and then begin again.”

— adrienne maree brown, “Loving Corrections”

As a child, I only knew of one Devil: the one who wanted me to suffer for eternity, the adversary and enemy of God. A once-devoted fallen angel, cast out of heaven for the crime of asking too many questions. The threat of hell hung heavy over my head—every lie told, every curfew missed, every rebellious thought damning me to endless torment. But as a kid who wanted to understand everything, who was constantly drawn to forbidden underworlds, who asked too many questions and challenged every answer, I’ve always had more sympathy for The Devil than those church leaders would’ve preferred.

The Devil seems more like a victim than a power player to me—after all, if The Devil’s job is to torture those who don’t submit to God’s orders, doesn’t that make this figure God’s instrument? As Esther Hamori wrote in God’s Monsters, “From the start, the divine Satan performs his corrosive duties thoroughly in service to God.” If The Devil’s purpose is to punish those who don’t follow God’s rules, isn’t this archetype ultimately God’s agent, God’s monster?

Eventually, like Lucifer, I found myself too uncomfortable within the church to stay. I started to discover many more Devils: tricksters and rebels, scapegoats and serpents, revolutionaries and disruptors, queers and weirdos. And as I discovered tarot, this figure became even more captivating: an archetype with endless layers of meaning and challenge, a figure designed for discomfort, a being of authenticity and exposure that pushes us to reckon with ourselves.

The tarot’s Devil whispers in our ear, seduces us into breaking free from the things that hold us back or keep us small. This is a Devil who can celebrate their alleged monstrosity, who wants us to be messy and wild and unapologetic in our freedom of self. This is a Devil who wants us to rip away the shrouds of conformity and colonialism, to become our most strange, beautiful, emotional, disorderly selves, to let our cries for justice and care ring out loudly instead of hiding in silence. This is a Devil who urges us to recognize our shame for what it is and leave it behind, tangled in old bindings, so that we can step freely forward with joy and courage into the people we were meant to be.

In asking what feels broken, what we are afraid to face, what we are reluctant to refuse, this Devil presses our tenderness until it bruises. There is pain in this, yes—but there is also pleasure in letting ourselves be seen and known, in reveling in our imperfections, in making our own power play.

This volume of The Rebis, an annual love letter to tarot presented as an anthology of creative writing and art, is not for the faint of heart. After last year’s hope-soaked issue on The Star, the much-feared Devil archetype might feel too heavy, too dangerous, too much. But as Rebis founder and editor

wrote to me in her pitch on this card, after spending “almost a whole year up in the heavens, dreaming Star dreams… I had a distinct vision of a star falling out of the sky.” We can’t look up to the gleaming dark forever—eventually, we must return to the dirt, to the Earth, to ourselves, and find out what we’re really made of.In asking what feels broken, what we are afraid to face, what we are reluctant to refuse, this Devil presses our tenderness until it bruises. There is pain in this, yes—but there is also pleasure in letting ourselves be seen and known, in reveling in our imperfections, in making our own power play.

Every contributor to this issue has passed through fire, spending real time with their demons and being transformed by their shadows. These offerings are revealing, intense, risky. What a brutally vulnerable thing, to drag one’s longings into the light and make something beautiful out of painful truths. It requires a tremendous amount of courage to walk with the Devil so openly, to leave footprints for others to follow.

In “Silencio,” Laetitia Barbier challenges our notions on certainty, and makes a case for a more Lynchian approach to riddles and reality. Clever and subversive fiction from Elizabeth Wing and [sarah] Cavar explore discomfort and rule-breaking, the truth that lives in crossing blurry lines. Sean Koa Seu’s “String Theory” urges us to consider what truly binds us to this world, and what it means to be bound to one another. Former Rebis editor

gives us permission to be our most beautifully monstrous and authentic selves, while considers what it means to watch and empower others to behave in monstrous ways. An interview with reveals potent truths about erotic wildness and necessary rupture, and the importance of imagining beyond what is too often presented as safe or ordinary.We were eager to include aspects of The Devil that would push readers to the edge, encouraging us to engage with questions that don’t have easy answers. Aliya Bree Hall and

share raw, intimate explorations of memory and truth, offering unflinching reflections of their own hauntings, while in “Confession,” Alessandra Nysether-Santos offers a prayer of redemption from the tangles of restricted and disordered eating. ’s “The Sweetness” lets us glimpse a tantalizing fantasy of gender-bending experimentation and manifestation. ’s “In Chains” thrusts us into a scene exploring dominance and the freedom of pain, while poems from , , and remind us that we, too, can unleash the monsters within ourselves in various ways.But we didn’t want to leave you without potential pathways forward. Jamie Michelle Waggoner walks us through “Praying The Devil’s Rosary,” providing a beautiful roadmap for connecting with the shadows that dwell within. Alm Lindsey suggests navigating the reality of the climate crisis through a lens of necessary exorcism, while

explores The Devil through a lived experience with punk music and counter-cultural rebellion. Stephanie Adams-Santos and Anna Barouh Davis lead us in an imaginative awakening, walking with us through the underworld of the self and introducing us to companions who offer courage and insight for the journey.To flip through these pages, to read these poems and essays, to view this artwork and participate in these rituals, is a sacrament, an act of communion. We’re deeply grateful to all of the contributors to this issue, more than I can mention here. Every sharp truth and flash of crimson, every glimpse at the strange, twisting shapes created by our brilliant Creative Director

and our talented contributing artists, reveals a new facet of this complicated, messy, potent, necessary archetype. This issue would not exist without all of you to read it, to question it, to struggle with it.The Devil can and will teach us to be brave, to be strong, to be wild. And this is the kind of courage we need to claim for ourselves, every single day—because the fascists running our country would prefer that we stay hidden and quiet, submissive and meek, that we do everything we can to obey and conform. They need us to bite back our words and our stories, to tremble in isolation, to not question or disrupt. They need us to look like them, sound like them, dress like them, and follow their every restriction. In working with The Devil, in being brave enough to explore and interrogate what we find hidden within ourselves, we remember what it means to disobey, to raise our voices together in a rowdy and rebellious chorus, to break rules and stay weird and illuminate all that they would prefer to keep hidden.

The Devil can and will teach us to be brave, to be strong, to be wild. And this is the kind of courage we need to claim for ourselves, every single day—because the fascists running our country would prefer that we stay hidden and quiet, submissive and meek, that we do everything we can to obey and conform.

We reclaim hell for ourselves, and stop fearing punishment from gods and their monsters. We become our own monsters, and share our courage amongst ourselves.

In a world filled with so much horror and violence and hatred, desire might feel greedy. Wildness could be too much of a risk. And authenticity may seem like a luxury few can afford. But resistance is a tapestry made from many threads—and yearning, satisfaction, and rebellion are all parts of that great weave, of building the world we want to inhabit and protect.

There is magic in the forbidden. There is truth buried in passion and longing. There is power lurking in pleasure. There is deliverance in confinement. There is courage in questioning. And when we're willing to sit with our lust and our shame in equal measure, when we're brave and bold enough to acknowledge all of the hunger that lives within us, when we’re ready to break through our bindings and reach for something more—those fractures and fissures are where we find true freedom. This is where we discover what we are made of, what we are fighting for, and put ourselves back together in even stronger, more beautiful ways.

Take The Devil’s perfectly monstrous hand, and let’s walk into the underworld together.

Guest Editor, The Rebis